Recordings

Songs from the Alan Lomax Collection

Songs from the Alan Lomax Collection

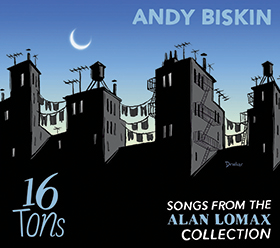

Andy Biskin and 16 Tons

Andy Biskin seeks to find the threads between old European folk music, early American songforms and the contemporary avant-garde. —Downbeat

Clarinetist and composer Andy Biskin, who has been hailed by The New Yorker as “ahead of the curve, long gifted at balancing his musical-Americana fixation with side trips into regions unexplored” turns his focus to legendary folklorist Alan Lomax. The CD features idiosyncratic instrumental interpretations of a dozen songs chosen from Lomax’s mammoth 1960 anthology, The Folk Songs of North America. Biskin takes an unorthodox approach, blending the tunes with his own melodies, Ellingtonian touches, marching band riffs, chamber music sonorities, four-part chorales, and the manic energy of cartoon music to create surprising versions of well-known favorites as well as more obscure ballads, hymns, and children’s game songs. The music is scored for clarinet, drums, and a choir of three trumpets.

Andy Biskin clarinet/bass clarinet

John Carlson trumpet

Dave Smith trumpet

Kenny Warren trumpet

Rob Garcia drums

Cover image by Eric Drooker

Design and hand lettering by Lizi Breit

“Songs from the Alan Lomax Collection” Liner Notes

Alan Lomax (1915-2002) had a profound influence on our understanding of American folk music. His legacy includes thousands of essential field recordings, as well as anthologies, essays, and groundbreaking research that seeks to unravel the very meaning of music within a culture. He was a tireless advocate for what he, way ahead of his time, termed cultural equity: giving all cultures an equal voice and promoting their diversity and preservation.

Alan came into my life when I was in my 20s. My first job right out of college was as his research assistant, and I spent a couple of monkish years poring over manuscripts and computer printouts in a dusty office on West 98th Street in Manhattan.

Alan was a bear-like presence—impulsive, intimidating, and wily—but also passionate, idealistic, and fearless. He had an uncanny knack for getting what he needed from people, often relying on a toothy, southern-gentlemanly smile that he would flash to charm a favor or make a point. He was a truly original thinker, and like many of that sort, he lived a messy a life, often relying on others to do the detail and clean-up work. I didn’t expect that to be what I’d be doing for him with my fancy anthropology degree, but it turned out to be a big part of the job.

I spent two years working with Alan and then I moved on. But over the years, I often sensed there was still some unfinished business. Sure, I was proud of and grateful for my association with him, and I loved telling colorful tales about the experience, but I couldn’t honestly say that I was a true-blue believer. There was just too much messiness: Had he exploited and patronized the musicians he recorded? Were there critical gaps in his scholarship? Was he dismissive of those outside his sphere, asserting he alone knew the “true path?” And perhaps most importantly, how was this music relevant to me as a player and composer? I was firmly entrenched in jazz—the more experimental the better—while Alan believed everything good about the music I loved had been worked out by 1930. And though I enjoyed listening to traditional and world music, I was put off by the pious folkie ethic that insisted that in order to be valid and authentic, performers had to adhere to some idealized, pure form of a style. I wanted to write and play music my own way.

So I did go my own way, checking in with Alan every few years, sometimes helping him sort out a computer glitch or technical issue with his research, until his health started to decline in the late 1990s. By this point there was renewed interest in his work. Alan’s daughter, Anna Lomax Wood, took up her father’s legacy, directing the Association for Cultural Equity, which helped bring many of Alan’s unfinished projects to fruition, including his visionary Global Jukebox. His trove of recordings were organized and reissued, finding young and passionate new listeners. Some of his records were even sampled for electronic dance music hits.

Gradually I found myself gravitating back into Alan’s orbit. I was continually crossing paths with his old colleagues and we swapped our stories. I was also hanging out more with musicians outside of my art-jazz bubble, sitting in at chaotic jam sessions with pickers, strummers, and fiddlers. I discovered by chance that many of my hand-scrawled work-notes had found a home in the Library of Congress as part of the Alan Lomax Manuscript Collection. And by one of those strange New York coincidences, I ended up living in the same building Alan had resided in when I knew him.

I was riveted by Johns Szwed’s incisive 2010 biography, Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World, and it revealed how little I knew about my former boss. When I met Alan, his career seemed in full flower; it was sobering to see that the period I knew him spanned only a few pages near the end of the book. Now, decades later, here I was tracing his pathway from a young man to middle age, as I simultaneously pondered how I’d covered those same years in my own life, and the role he had played in them. I realized the time had come to take another look at Alan’s legacy and see if I could find my own voice in the music he championed.

While I was working for him, Alan sometimes gave me copies of his records and books, often with warm, personal inscriptions. One such gift was his last big anthology, from 1960, The Folk Songs of North America. It’s a colossal tome, literally all over the map, which seems to be its intention. Here’s how Alan begins the introduction:

The map sings. The chanteys surge along the rocky Atlantic seaboard, across the Great Lakes and round the moon-curve of the Gulf of Mexico. . . From Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and New England, the ballads, straight and tall as spruce, march towards the West. Inland from the Sea Islands, slave melodies sweep across the whole South from the Carolinas to Texas. And out on the shadows of the Smoky and Blue Ridge mountains the old ballads, lonesome love songs, and hoedowns echo through the upland South into the hills of Arkansas and Oklahoma. There in the Ozarks the Northern and Southern song families swap tunes and make a marriage.

The book feels like a hybrid blend of songbook and scholarly survey. Alan selected 317 songs, grouped by region and genre; some are obvious and essential, others obscure and almost unplayable. There are straightforward piano arrangements, plentiful and fascinating song source notes, maps, pen and ink illustrations, a guitar and banjo guide, and a detailed discography. But at over 600 pages, it’s too unwieldy to prop on the upright for a family sing-along.

Alan begins the chapters with commentary on each song, sometimes writing about the song itself, at other times about its social, historical, or musical context. Most striking is his poetic introduction about the purpose and meaning of folk music. Here’s another excerpt:

The first function of music, especially of folk music, is to produce a feeling of security for the listener by voicing the particular quality of a land and the life of its people. To the traveler, a line from a familiar song may bring back all the familiar emotions of home, for music is a magical summing-up of the patterns of family, of love, of conflict, and of work which give a community its special feel and which shape the personalities of its members. Folk song calls the native back to his roots and prepares him emotionally to dance, worship, work, fight, or make love in ways normal to his place.

This idea that a people’s songs are inextricably correlated to their culture—“a magical summing up”—is the germ of Cantometrics, the cross-cultural research that would occupy the last decades of Alan’s life.

Like other things Lomax, The Folk Songs of North America is both an impressive and messy achievement. But, truth be told, I had scarcely ever glanced at it. It had been sitting idle on the bookshelf of every place I’d lived in since he gave it to me. Yet now as I embarked on this new journey, it somehow seemed right that I should use FSNA as my guidebook.

So I figured out a way to perch the thing on a music stand and started playing through the songs on my clarinet. I had no set agenda—I just wanted to see what bubbled up. It felt strange to be learning this music from a songbook. As I played the piano transcriptions it often felt like I was reading awkwardly translated poetry, and I had to seek out actual performances of the songs to make sense of them. Gradually I settled on a handful of tunes whose melodies grabbed me and seemed sturdy enough to for me to mess with. But how?

Alan had a genius for finding singers who not only gave us songs we’d never heard before, but also delivered intimate, unforgettable performances by infusing the words and melodies with all they knew and lived. The challenge I gave myself was to convey the essence of the music without a singer, using the instruments alone to carry the tunes. I wanted an ensemble that could mimic the call and response of a vocal group, that could play both gently and brash, that could sound relaxed and ragged or as tight as a dance band. For reasons I can’t quite explain, I settled on a line-up of clarinet, drums, and a choir of three trumpets. When I told people my idea, I got quizzical looks. Three trumpets? No guitar, banjo, or bass? No singer? Maybe later, I said.

The working method I arrived at was to intercut the songs with my own melodies and short improvisations. Sometimes the words suggested a direction. Sometimes I incorporated multiple versions of a tune, or phrases from related songs. Sometimes I just let the melody speak for itself. At the first rehearsal some things worked right off the bat, but there were still plenty of challenges: getting the clarinet to balance the brass, finding interesting ways to frame the improvised passages, figuring out how the drums could function as another voice, mastering the dark arts of trumpet mutes. But we gelled fast, and after a few gigs and it was hard to imagine it could ever be any other way.

I decided to call the band 16 Tons, after the Merle Travis classic, #154 in the book. We don’t play it yet, but we’ll get to it.

One of my favorite Lomax recordings is his Southern Journey, a 13-volume collection from around the same time as FSNA. For that series, Alan returned to many of the rural southern locales he had visited early in his career, excited to find new songs and singers. Alan always relished the fact that he and I were both displaced Texans living in exile in New York City, and I think of this CD as my own homecoming journey. I hope it proves to be a good travelling companion for you.

Big thanks to John, Rob, Dave, and Kenny for their patience, support, creativity, and inspired playing. Thanks to Oliver, who knew me then and now, for his sharp eye and ear, and to Olivier and Barbès for giving us a forum to work things out. Thanks to Limor and Amal for their invaluable feedback, encouragement, and overindulgence. And most of all, thanks to my Kickstarter community who banded together to make this recording happen.

The Songs

John A. Stone wrote the lyrics to Sweet Betsy from Pike in the 1850’s to a well-known English tune, “Vilikens and His Dinah.” The song chronicles the adventures of Betsy and her lover Ike, who cross the mountains from Missouri with Two yoke of cattle, a large yeller dog/A tall Shanghai rooster, and a one-spotted hog. They are seeking their fortunes in the California Gold Rush. By the 15th verse they’ve made it to El Dorado and are married and divorced. It’s a melody so perfect it needs no embellishment or accompaniment, and I use it to open and close this collection.

One of my earliest musical memories is hearing Burl Ives’s gentle version of Grey Goose (featured in the movie Fantastic Mr. Fox), especially his soothing “lord, lord, lord” refrain. But I also love Mike Seeger’s darker and edgier version, from the Seeger Family Animal Folksongs for Children. (We discovered that indispensable collection when our daughter was three, and for several years it was the soundtrack for every car trip.) The song depicts a hunting party run amok, with the goose surviving bullets, knives, and fire. For our rendition I jump between several versions of the melody, to underscore the sneakiness of that elusive bird. Alan says it’s a song about a people being stronger than their oppressors. (Full disclosure, this song, which was also recorded by Nirvana and Lead Belly, comes from another Lomax anthology, Folk Song U.S.A.)

Blue Tail Fly (“Jimmie Crack Corn”) was a minstrel song in the 1840s and a favorite of Abraham Lincoln’s. It was revived 100 years later during the folksong revival, and became a well-known children’s song. It was a big hit for the Andrews Sisters and Alan is said to have taught it to Burl Ives.

Our version begins with a northeastern ballad, Springfield Mountain, about a fatal rattlesnake bite that fells Timothy Merrick in 1761. There are other, better-known performances of Springfield, including Woodie Guthrie’s. Alan writes that this version was “recorded from the singing of J.C. Kennison, an itinerant Vermont scissor-grinder, 1939.”

Down in the Valley at first seems like a nostalgic, bucolic reverie, but it turns out to be the lament of a jealous, heartbroken lover, sung from his prison cell.

Down in the valley, valley so low,

Hang your head over, hear the wind blow.

If you don't love me, love whom you please,

But throw your arms round me, give my heart ease.

Write me a letter send it by mail

And back it in care of the Birmingham jail.

House Carpenter depicts a familiar folk theme: the demon lover. In this case he takes the form of a beguiling sailor who seduces the house carpenter’s wife, enticing her to sail away with him to “where the grass grows green on the banks of the Bittery.” The ballad, Alan writes, “represents the longings of pioneer women for love or an escape from their log cabin life—both sinful wishes to the Calvinist. The ballad’s heroine has one moment of romantic splendor. Then she is harshly punished.”

Go Fish is my own tune, loosely inspired by folk themes.

Lily Munroe tells the story of a girl who disguises herself as a man and rescues her sweetheart on the battlefield. It’s also known as “Lay the Lily Lo,” “Jack Munro,” and “Jack-a-roe,” and was recorded by the Grateful Dead and Joan Baez. The melody was repurposed in the 1940’s for the labor movement song, “Which Side Are You On?”

Tom Dooley is a North Carolina folk song about infidelity and revenge, based on the 1866 murder of Laura Foster by Tom Dula in Wilkes County. Several singers have been credited with the song’s rediscovery, each with their own direct family connection to the actual historical event. In 1958 it was a #1 hit for the Kingston Trio. For our version I’ve blended the jaunty 1929 Grayson and Whitter rendition with the sanitized Kingston Trio arrangement. We open with the trumpets imitating Doc Watson’s harmonica from my favorite recording of the song.

Muskrat is a children’s song, also known as “Rattlesnake,” collected from Aunt Molly Jackson. Jackson grew up in the coal mining culture of Harlan County, Kentucky, and worked as a midwife, folksinger, and union activist. It’s another favorite of my family’s from the from Seegers’ Animal Folksongs for Children.

Knock John Booker is an African American children’s game song. Alan’s father, John Lomax, recorded Aunt Molly McDonald singing it on a farm in Alabama in 1940, and as far as I can tell, there are no other available renditions. When you hear the lyrics you realize it’s a slave-era protest song. Alan writes, “‘Booker’ is another form of buckra, a word of African origin meaning ‘white’.”

Gon’ knock John Booker to the low ground

Tu-da darlin’ day

That lady bound to beat you,

Tu-da darlin’ day

Am I Born to Die is a hymn from the sacred harp shape-note tradition. It was published in 1817 and we stick pretty closely to the original, eerie four-part harmony.

Carl Sandburg included She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain in his 1927 collection, The American Songbag. It’s based on an old spiritual, “O Who Will Drive the Chariot When She Comes,” which describes the Rapture of the Second Coming. The tune is often associated with the railroad and there are also juicy Freudian interpretations. The song’s “she” was at one time thought to be Mother Jones, coming to organize the coal miners.