Recordings

Dogmental

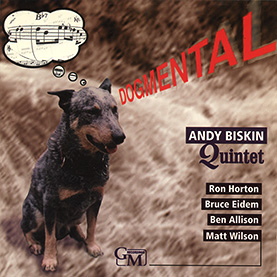

Dogmental

Andy Biskin Quintet

Andy Biskin's effervescent quintet slams neo-Dixieland, Jimmy Giuffre-esque chamber jazz, and Raymond Scott-inspired zaniness together and still finds plenty of room for inspired improvisation and offbeat composition. —The New Yorker

Andy Biskin's acclaimed debut album on Gunther Schuller's GM Recordings, "Dogmental" is scored for the traditional New Orleans frontline of clarinet, trumpet, and trombone, and features 15 Biskin originals that pick up where Dixieland leaves off. With Ron Horton (trumpet), Bruce Eidem (trombone), Ben Allison (bass), and Matt Wilson (drums).

—Read more Dogmental press clips here.“Dogmental” Liner Notes

A Producer’s Note

We met by chance in an elevator, Andy Biskin and I. He recognized me, and in the less than two minutes it took to get to our respective floors, I learned that he was a clarinetist, that he composed music, and led some kind of a chamber jazz group.

Some months later I received a tape containing a dozen Biskin compositions for a quartet of clarinet, trombone, bass, and drums. Receiving several dozens of tapes a year, usually of negligible interest, I was surprised to be more than impressed by what I heard. I was enchanted, amazed and intrigued to find music of such wonderful originality and sophisticated wit and humor. Humor in music is a rare commodity; often enough attempted, it also often fails. If not done skillfully, the music just remains bad and silly.

Like humor itself, it must be approached ‘seriously’ and ‘perfectly,’ and timing is everything. Like humor itself, it is best based on ordinary, common situations turned loose by clever distortion, exaggeration, surprise and a chaplinesque love of the subject. Biskin’s music here is based on thrice-familiar musical objets trouvé (“found objects,” as the French have it), which are then twisted and reshaped into comic creatures, to lead their own lives. Such manipulations have to be done subtly and concisely, with a fine, precise edge, offspring of both the intellect and emotion. Anything less than that, the music becomes merely obvious and vulgar, a mish-mash of trite cliches. We are here not in the world of guffaws, but of wry chuckles and inner delights.

I think Biskin treads this fine line brilliantly, and in his way associates himself—I don’t mean consciously nor (worse) self-consciously—with such great earlier genres as the best Hollywood cartoon music, the choicest Raymond Scott and Spike Jones, and even earlier the witty, scintillating scores of Georges Auric in France in the 1930s for the films of Rene Clair (A Nous la Liberté) and Cocteau’s 1928 Italian Straw Hat.

While using well-known, simple forms and materials—march (Flim Flam), polka (Sad Commentary), waltz (Rondel), Latin tinges (Brunching at the Bistro)—there is even a brilliant mariachi bit, delivered by Ron Horton, in Flim Flam—Biskin’s music is transformed into marvelous jazz by the players’ improvisations, contributions that almost miraculously amplify Biskin’s own harlequinades.

In his own playing, for all its originality, Biskin pays loving unslavish tribute to his clarinet forebears Pee Wee Russell and Jimmy Guiffre, just as Bruce Eidem delights in reminding us of everyone from Tricky Sam Nanton to Lawrence Brown to Urbie Green, and Ron Horton the likes of Lee Morgan. And how subtly yet enterprisingly both rhythm sections contribute to the ‘Biskin effect.’

Whether in the sudden ‘wrong notes’ as in Field Days; the theory lessons in ‘augmentation’ and ‘diminution’ (expanding and shrinking materials) as in Laughing Stock; the haunting balladry of Little Elsa; in the rousing virtuosity of No Bones and Off Peak; the outright zaniness of Dogmental, the lacerating raucous outbursts in Rondel; the delicious repetitiveness of Laughing Stock—I feel that Biskin gets it right all the time, with superb timing and exquisite taste.

Here I’ve told you why I felt compelled to produce this delectable CD. Now it’s your turn. I truly hope you will find in it the same pleasures I did.

— Gunther Schuller

Andy's Notes

When I was 15 I wanted to have my own band. But what kind of band? All my friends had rock bands, but I played the clarinet, and there were no clarinets in rock bands.

I started playing when I was nine. That was the year my father, the timpanist with the San Antonio Symphony, brought home a plastic Bundy model and left it on my bed for me to discover one day after school. I didn't know what it was but I was intrigued with the shiny keys, the reeds, the smell of cork grease, and most of all, how you had to assemble it like a kit before playing it. "This is a clarinet," my father said. "It is to be your instrument." The moment was heavy with prophecy and wonder.

Private lessons, marching band, solo and ensemble contest, duets with my mother on piano. But what about my band? One Saturday afternoon, while scouring through the moldy stacks of Southern Music, a venerable publishing house in downtown San Antonio, I came upon a batch of arrangements for two clarinets, trumpet, trombone, and tuba. There were polkas and waltzes, marches, even light classics like "Poet and Peasant Overture." Each booklet cost seventy cents; a set of five was three dollars.

One of the booklets was called "The Hungry Five." I quickly adopted the name and recruited four renegades from the school band. We set to work learning the music and memorizing the impossibly corny jokes and band schtick included in the front of the booklets. Soon we had a Hungry Five savings account, uniforms (white dress shirt, Boy Scout shorts, loud socks, suspenders), and were playing parties, high school talent shows, and the local Wurstfest.

Inside the front cover of each booklet was printed the following: "It is suggested that the compositions be played first in true classic manner and, when properly mastered, liberties may be taken for added effects." Though the terms "liberties" and "added effects" were left undefined, we soon figured out a way to make the music our own.

It was only recently that I realized how little my current band has strayed from sensibilities of the old Hungry Five. For several years I had a quartet with Bruce Eidem on trombone, Andy Eulau on bass, and Bruce Hall on drums. The main inspiration for this configuration was the incredible Steve Lacy/Roswell Rudd band from the sixties. Four tunes from the quartet included here.

Three years ago I added Ron Horton's trumpet to the band and started working with Ben Allison and Matt Wilson. My original idea was to update the traditional New Orleans style, using the same front line of trumpet, clarinet, and trombone. But something different seems to have emerged, and now when I take inventory of our repertory, I'm surprised at the preponderance of polkas, waltzes, marches, and little tone poems over "pure jazz" tunes.

The 15 compositions on this album were written over the last eight years. Most of them were first performed at the Cornelia Street Cafe. The club, which occupies a narrow, resonant basement room below a Greenwich Village restaurant, was the first to book the band, and it's still one of our favorite places to play.

For every performance I try to bring in a couple of new tunes. Somehow, just by imagining the band on the bandstand, with sound of each player in my ears, I'm inspired to come up with something new. Some pieces work right out of box, others may take a while to settle in, while still others get played once with much hooplah, and then are never mentioned again.

But what could be more thrilling than to work late into the night cooking up melodies, harmonies, and rhythms for these wonderful musicians, printing up the parts, gathering together the players, and then, in the true Hungry Five spirit, performing the tunes knowing that "liberties may be taken for added effects."

— Andy Biskin